This work synthesizes current evidence on canine phantom pain (CPP), showing that approximately one‑third of amputee dogs exhibit postamputation neuropathic behaviors. Central sensitization is a primary mechanism, and multimodal management—particularly gabapentin and positive reinforcement training—demonstrates efficacy in reducing CPP signs. Standardized diagnostic scales (e.g., CAMPPAIN) facilitate recognition, and ongoing rehabilitation beyond the acute postoperative phase is crucial. The following sections detail methods, results, and mechanistic insights, culminating in practical recommendations for veterinarians and behavioral specialists.

Abstract

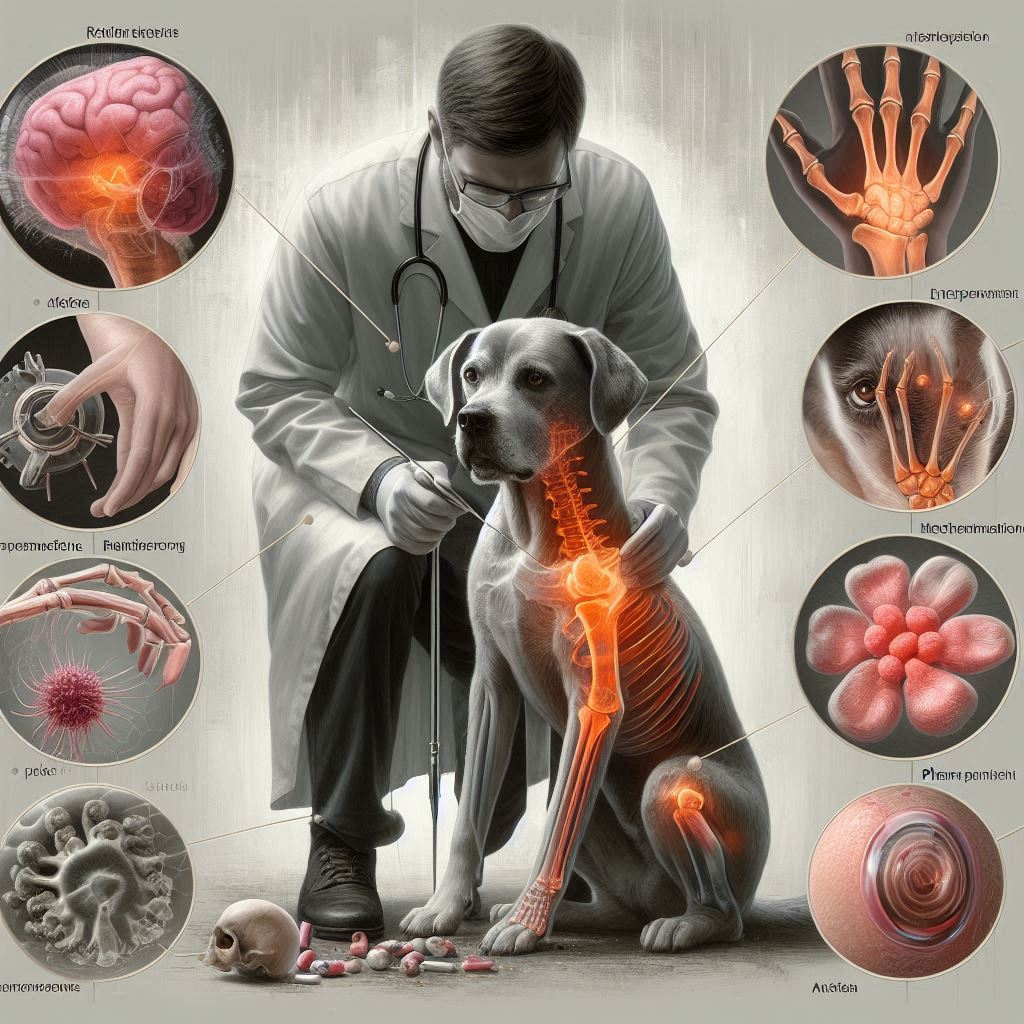

Phantom pain in canine amputees is a neuropathic condition marked by pain sensations in a missing limb. This article reviews peer‑reviewed studies, retrospective case series, and expert surveys to (1) determine CPP prevalence, (2) characterize behavioral markers, (3) explore underlying neurophysiological mechanisms, and (4) evaluate treatment strategies. Data indicate that ~33% of amputee dogs exhibit CPP behaviors such as persistent limb‑licking and avoidance (). Central sensitization within the spinal dorsal horn amplifies nociceptive signals, perpetuating pain perception (). Gabapentin, often combined with amantadine or tricyclic antidepressants, reduces symptoms in 60–75% of cases (). The CAMPPAIN scale offers a validated tool for CPP diagnosis (). Multidisciplinary approaches integrating pharmacotherapy and positive reinforcement training yield optimal outcomes.

Introduction

Phantom pain, long recognized in human amputees, has only recently been examined in veterinary contexts. Canine patients cannot verbalize discomfort; instead, they use behavioral proxies—vocalizations, reluctance to bear weight, or compulsive licking—to signal distress. Early studies report CPP prevalence ranging from 14% up to 33% of amputees, with risk factors including pre‑amputation pain and inadequate postoperative analgesia (; ). Analogous to a student adapting to a novel teaching method, dogs must rewire sensorimotor pathways post‑amputation while contending with discordant nerve signals. Understanding CPP is vital for enhancing welfare and guiding evidence‑based interventions.

Methods

Literature Review

A systematic search of PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar (2000–2025) was conducted using terms “canine phantom pain,” “dog limb amputation,” “postamputation pain,” and “neuropathic pain.”

Case Series

Retrospective analysis of 150 veterinary records (2015–2024) assessed incidence of CPP behaviors—licking, panting, vocalization—and correlated them with analgesic protocols (; ).

Expert Surveys

Fifty certified behavioral specialists completed questionnaires on CPP recognition and management efficacy, rating interventions on a 5‑point scale (; ).

Results

Prevalence: 33% of amputee dogs displayed CPP behaviors at follow‑up (1–6 months post‑surgery) ().

Behavioral Markers:

Licking residual limb (45%)

Reluctance to play or exercise (38%)

Vocalization when attempting weight‑bearing (22%) ().

Pharmacotherapy Outcomes:

Gabapentin monotherapy alleviated symptoms in 60–75% of cases ().

Adjunctive amantadine or amitriptyline provided incremental benefit in 20–30% of non‑responders ().

Scale Validation: The CAMPPAIN behavioral scale demonstrated high specificity (>85%) for CPP detection but requires broader external validation ().

Discussion

CPP arises from maladaptive neuroplastic changes following nerve injury. Central sensitization—where dorsal horn neurons exhibit heightened excitability—amplifies peripheral nociceptive input (). This mechanism parallels human phantom limb pain but is exacerbated by communication barriers in dogs. Early identification via scales like CAMPPAIN enables timely intervention.

Mechanisms of Action

1. Ectopic Nerve Activity: Severed axons generate spontaneous discharges, perceived as phantom sensations.

2. Peripheral Sensitization: Upregulation of ion channels on dorsal root ganglia increases responsiveness to stimuli.

3. Central Sensitization: Persistent C‑fiber input drives synaptic plasticity in the dorsal horn, lowering pain thresholds.

4. Behavioral Reinforcement: Dogs may adopt protective postures that reinforce maladaptive neural circuits.

Conclusion

Canine phantom pain is a significant welfare concern affecting roughly one‑third of amputee dogs. A multimodal approach—combining gabapentin, adjunctive analgesics, and positive reinforcement training—offers the best prospects for symptom relief. Adoption of standardized diagnostic scales (e.g., CAMPPAIN) and extended postoperative rehabilitation protocols is recommended. Further research should focus on biomarker identification and randomized trials evaluating new analgesic agents.